When I was 5 years old, the police told my parents that my twin sister had di3d in the woods behind our house.

I never saw her body. I never saw a casket. I was never taken to a grave.

There was only a closed door, hushed voices, and a silence that settled over our family like dust that never quite lifted.

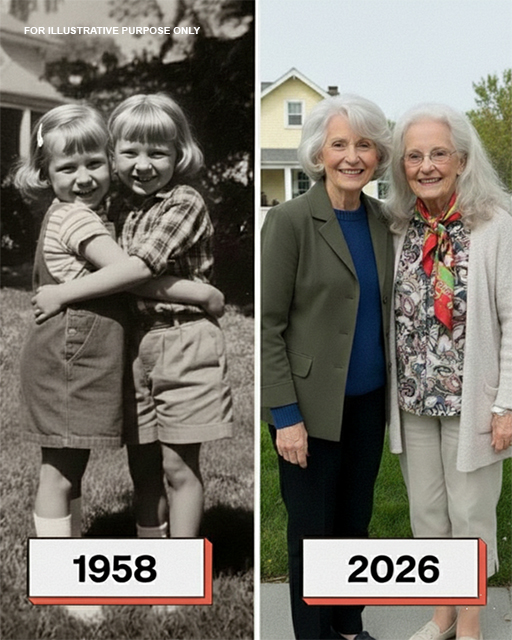

My name is Dorothy. I am 73 years old, and for most of my life, I have carried the outline of a missing child inside my chest. Her name was Ella.

Ella and I were not simply twins in the technical sense. We were the kind who shared everything: bedroom, clothes, secrets, fears. If I scraped my knee, she cried louder than I did. If she got in trouble, I felt guilty.

We had identical smiles and identical cowlicks that refused to lie flat, no matter how much water our mother smoothed over them. Ella was fearless. I was cautious. She ran ahead. I followed.

The day she disappeared was gray and damp. Our parents were at work, and we were staying with our grandmother in the small white house where our mother had grown up.

I remember lying in the spare bedroom with a fever, my throat raw and my skin too hot. Grandma sat beside me with a cool cloth, murmuring that I would feel better soon.

“Just rest, sweetheart,” she said. “Ella will play quietly.”

Ella was in the corner of the room, bouncing her red rubber ball against the wall and humming to herself. Thump. Thump. Thump. The steady rhythm mixed with the sound of rain tapping against the windows.

I must have fallen asleep.

When I woke up, something was wrong. The house felt hollow, as though all the air had been sucked out of it. The rain had stopped. The room was too quiet.

No ball. No humming.

“Grandma?” I called.

She did not answer right away. When she finally rushed in, her hair was disheveled and her face drawn tight in a way I had never seen before.

“Where’s Ella?” I asked.

“She’s probably outside,” she said quickly. “You stay in bed, all right?”

Her voice trembled.

I heard the back door open and slam. Then her voice, sharper this time, calling Ella’s name into the yard.

Minutes later, though in my memory they stretched endlessly, there were more voices. Neighbors. The creak of the front door. Someone is walking quickly across the hardwood floor.

I slipped out of bed and padded down the hallway. The house felt colder than it should have. In the living room, our neighbor, Mr. Abrams, knelt in front of me.

“Have you seen your sister, honey?” he asked gently.

I shook my head.

Soon after, the police arrived. I remember blue jackets damp from the rain, heavy boots leaving marks on the floor, radios crackling. They asked questions I did not understand.

“What was she wearing?”

“Where does she usually play?”

“Has she ever talked to strangers?”

I could barely answer. I kept thinking she would burst in through the back door at any moment, laughing because this had all been some kind of game.

They searched the strip of woods behind the house. People in our town liked to call it “the forest,” though it was really just a thick cluster of trees stretching a few acres deep.

That night, flashlights bobbed between trunks slick with rain. Men shouted her name until their voices turned hoarse.

They found her red ball.

That was the only detail anyone ever shared with me clearly.

The search lasted days. Then weeks. I remember neighbors bringing casseroles, the smell of coffee constantly brewing in the kitchen, hushed conversations that stopped whenever I entered the room.

Grandma cried at the sink when she thought I could not see her. “I’m so sorry,” she whispered over and over.

Finally, one evening, my parents sat me down in the living room. My father stared at the carpet. My mother twisted a handkerchief in her hands.

“The police found Ella,” my mother said softly.

“Where?” I asked.

“In the woods.”

“Can I see her?”

My father’s jaw tightened. “No.”

“Is she coming home?”

My mother’s eyes filled with tears. “She’s gone.”

“Gone where?”

“She di3d,” my father said. His voice was firm in a way that ended all further questions. “Ella di3d. That’s all you need to know.”

I do not remember a funeral. I do not remember a grave. I do not remember being allowed to say goodbye.

One day, I had a twin.

The next day, I was alone.

Ella’s toys disappeared from our bedroom. Our matching dresses vanished from the closet. Her name was never spoken again in our house. It was as if she had been erased with a careful hand.

At first, I kept asking.

“Where is she buried?”

“What happened?”

“Did it hurt?”

Each time, my mother’s face seemed to harden. “Stop it, Dorothy,” she would say. “You’re hurting me.”

I wanted to shout that I was hurting too. But I learned quickly that grief, in our home, was something to be swallowed.

I grew up that way: polite, quiet, outwardly well adjusted. I did my homework, made friends, and kept my questions to myself. Inside, there was a constant buzzing emptiness, a space shaped exactly like my sister.

When I was sixteen, I walked into the local police station alone.

“I’d like to see the case file for my sister,” I said to the officer at the front desk. “Her name was Ella Hale. She disappeared eleven years ago.”

He looked at me with something like pity. “How old are you?”

“Sixteen.”

He sighed. “Those records aren’t open to the public. Your parents would have to request them.”

“They won’t even say her name,” I said. “They just told me she di3d.”

He softened but did not budge. “Sometimes it’s better to let sleeping dogs lie.”

I left feeling foolish and more isolated than ever.

In my twenties, I tried one last time with my mother. We were folding laundry together when I said quietly, “I need to know what really happened to Ella.”

She went still.

“What good would that do?” she whispered. “You have your own life now.”

“I don’t even know where she’s buried,” I said.

“Please,” she replied, her voice breaking. “Don’t ask me again. I can’t.”

So I stopped asking.

Life carried me forward. I finished college, married a kind man named Richard, and became Dorothy Hale Morgan. I had two children and later grandchildren. I built a life that, from the outside, looked full.

But sometimes I would set the table and hesitate, as if expecting another plate to be needed. Sometimes I would look in the mirror and imagine another face beside mine, aged and lined but unmistakably the same.

My parents di3d within three years of each other. They took their silence with them.

For decades, I told myself that was the end of the story.

Then my granddaughter, Lillian, was accepted into a university several states away.

“Grandma, you have to come visit,” she insisted. “You’ll love it.”

A few months later, I flew out to see her. After helping her settle into her dorm, she shooed me away the next morning.

“Go explore,” she laughed. “There’s a café around the corner. Best coffee in town.”

So I went.

The café was warm and crowded, with mismatched chairs and the scent of roasted beans hanging in the air. I stood in line, studying the chalkboard menu.

Then I heard a woman’s voice at the counter.

It was low and slightly raspy, with a cadence that made my stomach tighten. It sounded like my own voice recorded and played back.

I looked up.

The woman turned.

For a moment, I felt as though I had stepped outside my body.

She had my face.

The same slope of the nose. The same arch of brows. The same faint crease between her eyes. Her hair was gray and pinned up loosely, just as mine often was.

We stared at each other.

“Oh my God,” she whispered.

I walked toward her without thinking. “Ella?” I breathed.

Her eyes widened. “My name is Margaret,” she said.

I flushed. “I’m so sorry. My twin sister disappeared when we were five. I’ve never seen anyone who looks like me like this.”

She swallowed. “You don’t sound crazy. I was just thinking the same thing.”

We sat down together, our coffee forgotten.

Up close, the resemblance was uncanny.

“I was adopted,” she said slowly. “My parents always told me I was chosen, but they never gave details. If I asked about my birth family, they shut it down.”

My pulse pounded.

“What year were you born?” I asked.

She told me.

It was five years before my own birth year.

“We’re not twins,” I said carefully.

“No,” she agreed. “But that doesn’t mean we’re not connected.”

We exchanged phone numbers, both of us shaken.

Back home, I found myself thinking of a dusty box in my closet filled with my parents’ old documents. I had never examined it closely.

I dragged it onto my kitchen table and began sorting through its contents: tax returns, medical records, faded letters.

At the very bottom lay a thin manila folder.

Inside was an adoption document dated five years before my birth.

Female infant. No name listed.

Birth mother: my mother.

Behind it was a folded note in my mother’s handwriting.

I was young and unmarried. My parents said I had brought shame. They told me I had no choice. I was not allowed to hold her. I saw her only once, from across the room. They told me to forget, to marry, to build a proper life. But I will never forget my first daughter.

My vision blurred with tears.

Margaret was not my twin returned from the woods.

She was my older sister.

I sent her photos of the documents. She called immediately, her voice trembling.

“Is this real?” she asked.

“It’s real,” I said.

We did a DNA test to be certain. The results confirmed what our faces already knew. We were full siblings.

The revelation did not feel like a fairy tale reunion. It felt like uncovering the wreckage of three lives.

My mother had given birth to a daughter she was forced to surrender her. Years later, she had twin girls. One she lost in the woods. One she kept and wrapped in silence.

Margaret and I began talking regularly. We compared childhoods. She had grown up loved but always slightly aware of a missing piece. I had grown up in a house haunted by a name no one dared to speak.

We were not suddenly inseparable. You cannot compress nearly seven decades of separate lives into instant closeness. But we built something steady and real.

As for Ella, the twin I lost, her absence remains part of me. I still do not know every detail of what happened in those woods. Perhaps I never will.

But I understand my mother differently now.

Pain does not excuse secrecy. It does not undo the harm of silence. Yet I can see how a young woman, shamed into surrendering her first child, might have buried that grief so deeply that when tragedy struck again, she could no longer speak at all.

She loved her three daughters.

One she was forced to give away.

One she could not save.

One she kept but did not know how to comfort.

Meeting Margaret did not erase the hole shaped like Ella. But it changed the shape of my story. I am no longer the sole survivor of a pair. I am one of three sisters, bound by loss, by secrecy, and finally by truth.

At seventy-three, I have learned that even the longest silence can be broken. When it does, what you find beneath it may not be simple or painless. But it can still be a kind of grace.