When my father passed away, the farm came to me.

It wasn’t a surprise; he had told me for years that one day it would be mine. Still, standing on that land after his funeral, the fields stretching toward the horizon and the old barn sagging in the middle of it all, I felt less like an heir and more like a trespasser. The silence of the place pressed on me, heavy and suffocating.

My father, Robert, had been a hard man. He wasn’t cruel exactly, but stern, reserved, someone who measured his words carefully and offered affection in brief, awkward gestures rather than warm declarations. I grew up under the impression that the farm meant more to him than it did, and perhaps in some ways, that was true. The land was his life’s work, his pride, his purpose.

Cleaning out his house after the funeral was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. His smell still clung to the furniture, to the coats hanging by the door, to the old leather chair in the living room. Every drawer I opened seemed to rattle with ghosts: his receipts carefully filed away, old tools with handles worn smooth, letters from neighbors dating back decades.

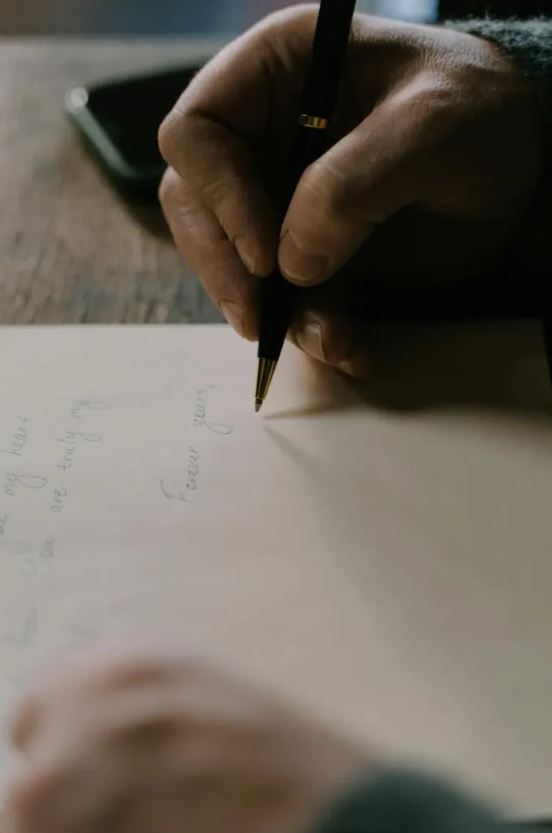

And then, in the bottom drawer of his desk, I found the envelope.

It was addressed to me in his sharp, angular handwriting, sealed with tape yellowed by time. My stomach twisted as I pulled it open. He hadn’t been one for sentimental words, so the fact that he had left me a letter at all was startling.

The note inside was brief, almost blunt:

If you are reading this, it means I am gone. There is something you should know about the farm. The land you now own was not truly mine to give. Years ago, I made a choice that hurt others. I carried that secret to my grave, but I cannot rest without telling you. The truth is in the box beneath the floorboards in the barn. You’ll find the loose plank under the west window. Be careful who you share this with. Some wounds never healed.

My hands shook as I folded the letter back up. What did he mean the farm wasn’t his to give? What secret had he carried all these years?

The next morning, I walked out to the barn. The air was cool, heavy with the scent of hay and oil. Dust motes spun in the slanted light. My boots creaked against the wood as I crossed to the west wall.

It didn’t take long to find the loose plank. My heart pounded as I pried it up with the back of a hammer. Beneath, sure enough, was a small wooden box, weathered but intact.

Inside were papers, old deeds, letters, and a faded photograph of two young men standing side by side in front of the barn. One was my father, unmistakably him, despite the smoothness of youth. The other was a man I didn’t recognize: taller, broad-shouldered, with a grin that contrasted sharply with my father’s solemn stare.

The letters told the story.

The other man was Henry Walker, my father’s best friend since boyhood. They had grown up together, worked the land together, dreamed of building a farm side by side. The land had belonged to Henry’s family for generations. But when Henry went off to f.i.g..ht in Vietnam, things changed.

According to the letters, while Henry was overseas, his parents struggled financially. Debts piled up, and the bank threatened foreclosure. My father stepped in not to help, but to take. He bought the land at a fraction of its value, fully aware that Henry’s parents had no choice.

When Henry came back from the w..a..r, he returned to find the farm no longer his. The betrayal was devastating. He and my father had a v.i.o..l..ent falling out, and Henry left town soon after.

One letter, written by Henry himself and never sent, cut me to the bone:

You knew this place was ours. You knew it was supposed to be my future. I b..l..e..d in a jungle while you signed papers behind my back. You didn’t just take land, Robert, you took everything I had left to come home to. I can never forgive you.

I sat on the barn floor for a long time, the letters spread out before me. My father had built his entire life on another man’s loss. The farm that everyone admired, the work that defined him, was rooted in betrayal.

Suddenly, so many things made sense: the bitterness I’d noticed in certain neighbors’ voices when they spoke my father’s name, the unexplained hostility from the Walker family whenever our paths crossed, the cold stares I couldn’t decipher as a child.

I decided I needed to know more.

That evening, I drove into town and stopped at the local diner, where old farmers still gathered every morning for coffee and gossip. When I asked about Henry Walker, the place went quiet.

“Henry doesn’t come around here much,” one man finally said. “Moved out west years ago. Can’t say I blame him. Place holds too many bad memories.”

Another muttered, “Your daddy and him… they had bad b.l.o..od. Nasty business.”

I pressed gently, but no one wanted to give details. The silence was louder than words.

Back at the farm, I couldn’t sleep. I kept picturing Henry coming home from w..a..r, expecting to see his family’s farm, only to find my father standing there with the deed. The thought made me sick.

Over the following weeks, I tried to track Henry down. It wasn’t easy; he had moved states away and changed addresses more than once. Finally, through a mutual acquaintance, I got a phone number.

When I called, a gravelly voice answered. “Hello?”

“Mr. Walker? This is Daniel Miller… Robert’s son.”

The silence on the other end stretched so long I thought he’d hung up. Then: “What do you want?”

I swallowed. “I found something. Letters. Papers. I think… I think my father wronged you. And I wanted to hear your side.”

Another pause, then a sigh. “Come see me. But don’t expect me to sugarcoat it.”

I drove six hours the next weekend to a modest house on the edge of a small town. Henry was waiting on the porch. His hair was white, his frame stooped, but I recognized the man from the photograph. His eyes, sharp and piercing, were the same.

Inside, over coffee, he told me everything.

He had trusted my father like a brother. They’d worked side by side for years, dreaming of raising their families on that land. When he was drafted, he asked my father to look after his parents, to make sure they were all right.

Instead, my father seized the opportunity. Bought the land cheap, left Henry’s parents destitute. They moved away not long after, broken and bitter. His mother d.i.e.d within a year.

“When I came back,” Henry said, his voice rough, “I was different. The w..a..r had already hollowed me out. But I thought at least I had home. Turns out I had nothing. Your daddy told me it was just business. That I should understand. But there are things a man can’t forgive.”

His eyes glistened, though his face remained hard. “I lost everything: family, land, and future. I wandered for years after that. D.r..a..nk too much. Got in f.i.g..hts. Made a mess of my life. And every time I thought about trying to rebuild, all I could see was that farm, sitting in your family’s hands.”

I didn’t know what to say. Apologies felt meaningless, like trying to mend a shattered window with tape.

Still, I said the only thing I could: “I’m sorry. I can’t change what he did. But I don’t want to pretend it didn’t happen.”

Henry studied me for a long time. Finally, he said, “At least you had the guts to come here. Your father never did.”

When I left his house, I felt a strange mix of relief and grief. I’d found the truth, but it didn’t free me; it shackled me with a responsibility I hadn’t asked for.

Back at the farm, the land no longer looked the same. Every fence post, every tree line carried the weight of betrayal. The neighbors’ coldness wasn’t just about my father—it extended to me now, the son who had inherited stolen ground.

I considered selling the place, washing my hands of it. But part of me wondered if leaving would be another form of running away, just as my father had run from the truth.

In the end, I decided the farm shouldn’t just be mine. I reached out to Henry again. I offered him a share of the land, or at least a lease so he could use it as he wished. At first, he resisted. “What’s done is done,” he said. “I don’t need your charity.”

“It’s not charity,” I insisted. “It’s restitution. My father took this from you. I can’t undo that, but I can try to give something back.”

After weeks of back and forth, he agreed to farm a small section, just a few acres, enough to plant what he wanted. Watching him walk those fields for the first time in fifty years, I saw something soften in his posture.

We didn’t become friends overnight. Trust wasn’t something that could be rebuilt quickly. But slowly, cautiously, we found common ground. He taught me things about the land that even my father had never shared. He told me stories about the farm before the bitterness, about laughter in the fields, about hope.

And I realized then that the farm had held more than one life all along. It had held dreams, betrayals, losses. It had been destroyed, and it had been sustained.

My father’s choice had ruined more than one life. But maybe just maybe mine could help heal what was left.