For six months, my life revolved around a single room at St. Catherine’s Medical Center, the steady rhythm of machines, and a man I never invited but could not ignore.

My name is Claire Morgan. I was 42 years old when my 17-year-old daughter, Iris, was put into a coma by a drunk driver.

Before that, my life had been ordinary in the quiet, forgettable way that only becomes precious once it’s gone. I worked part-time from home. I worried about groceries and laundry. I argued with my husband, Paul, about nothing that truly mattered. Iris worked afternoons at a small independent bookstore downtown, saving for college, forever complaining that the cash register stuck and the coffee machine leaked.

Six months ago, she was driving home from that bookstore when a pickup truck ran a red light five minutes from our house and slammed into the driver’s side of her car.

I didn’t see the accident. I arrived after the road was already blocked, and a police officer held up his palm and told me to stay back. I remember screaming her name anyway, as if volume could bend rules or physics.

Now Iris lived in Room 223.

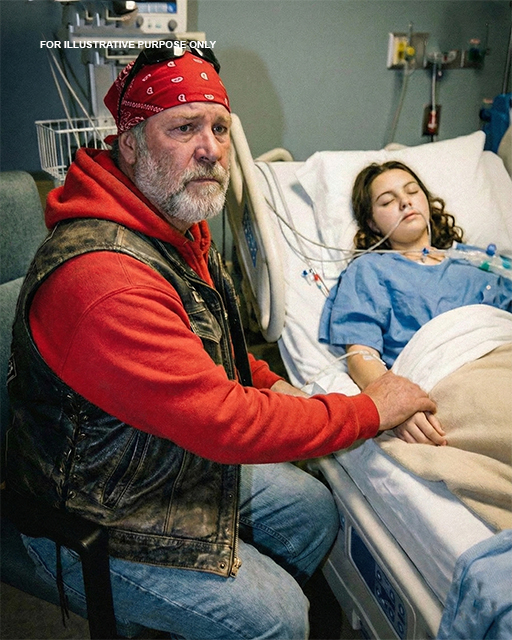

She lay surrounded by machines I had never wanted to understand. Tubes. Lines. Monitors. I learned what every beep meant, which alarms mattered, and which didn’t. I slept in a vinyl recliner that never quite reclined. I ate crackers from vending machines and drank hospital coffee that tasted like regret. I knew the schedule of every nurse, and which ones tucked blankets tightly and which ones simply draped them.

Time in a hospital doesn’t move normally. It becomes a loop. A wall clock. Footsteps in the hallway. The quiet hum of oxygen.

And every single day, at exactly 3:00 p.m., the same thing happened.

The door to 223 would open.

A large man would step inside.

The first time I saw him, I thought he was lost. He was enormous, tall and broad-shouldered, built like someone who carried engines for fun. He had a gray beard that reached his chest, worn boots, and a leather vest with faded patches stitched onto it. His arms were inked with tattoos that disappeared beneath rolled sleeves. His hands looked permanently bruised, his knuckles scarred and thick.

He didn’t look angry.

He looked tired.

He would nod to me, always politely and always briefly, as if afraid to intrude. Then he would walk straight to Iris’s bed.

“Hey, kid,” he’d say softly. “It’s Ray.”

Sometimes he brought a book. A fantasy novel with dragons and maps, battered paperbacks I recognized from Iris’s shelves at home. Other days, he just talked. Quietly. Like she could hear him.

Nurse Elise always smiled when she saw him.

“Afternoon, Ray,” she’d say. “Want coffee?”

“If you’re offering,” he’d reply.

Like this was normal. Like he belonged there.

He’d sit beside Iris, take her hand carefully between both of his, and stay exactly one hour. Not fifty-five minutes. Not an hour and ten. At 4:00 p.m. on the dot, he’d place her hand back on the blanket, nod once at me, and leave.

Every day.

At first, I didn’t say anything.

When your child is in a coma, you don’t question kindness. You cling to it like driftwood. If a stranger wants to talk to her, hold her hand, believe she’s still someone worth speaking to, who was I to push that away?

But weeks passed.

Then months.

I started to notice the way he spoke to her, as he knew her. Like he carried his own guilt into that room and laid it at her bedside every afternoon.

“Today wasn’t great,” I heard him murmur once. “But I stayed sober. So that’s something.”

That night, I couldn’t sleep.

I asked Iris’s friends if they knew him. They didn’t. I asked my husband. He shook his head, confused. The nurses, however, treated Ray like furniture: permanent, familiar, unquestioned.

Finally, one afternoon, I asked Elise quietly, “Who is that man?”

She hesitated, just long enough for my stomach to tighten.

“He’s… someone who cares,” she said carefully.

That answer didn’t satisfy me. It made things worse.

I was the one signing consent forms. The one sleeping in the chair. The one watching my daughter breathe and praying it didn’t stop. And yet some stranger was holding her hand every day as if it were his right.

So the next afternoon, when Ray left at four, I followed him into the hallway.

“Excuse me,” I said. “Ray?”

He turned.

Up close, he was even bigger. His eyes were bloodshot, rimmed with exhaustion, but gentle. He looked like a man who hadn’t slept well in years.

“Yes?” he said.

“I’m Iris’s mother.”

“I know,” he replied. “You’re Claire.”

That stopped me cold.

“You know my name?”

“Elise told me,” he said. “She also told me not to bother you unless you wanted to talk.”

“Well,” I said, my voice shaking, “I’m talking now.”

We sat in the waiting area, two molded plastic chairs bolted to the floor.

“I’ve seen you here every day,” I said. “For months. You hold my daughter’s hand. You talk to her. I need to know who you are and why you’re here.”

He closed his eyes briefly, as if bracing himself.

“My name is Ray Carter,” he said. “I’m fifty-eight. I’ve been married to my wife, Nadine, for thirty-two years. I have a granddaughter named Willow.”

I waited.

“And?” I said.

He swallowed hard.

“I’m the man who hit your daughter,” he said quietly. “I was the drunk driver.”

The world went silent.

“It was my truck,” he continued. “I ran the light.”

I stood up so fast my chair screeched.

“You have some nerve,” I said, my hands shaking. “You put my child in a coma, and then you sit with her like—like—”

“I pled guilty,” he said gently. “Ninety days. Lost my license. Court-ordered rehab. AA. I haven’t had a drink since that night.”

He didn’t argue. He didn’t defend himself.

“But she’s still in that bed,” he said. “So none of that fixes anything.”

I told him to leave. I told him I should call security. He nodded, accepting it all without protest.

“The first time I came,” he said, “was the day after I got out. I needed to see her. Not just the paperwork.”

He told me how the doctor initially refused him. How he sat in the lobby for hours. How Elise finally let him in while I was meeting with a social worker.

“I come at three,” he said, “because that’s when the accident happened.”

I went back to Iris’s room, shaking.

For the first time in six months, three o’clock came, and the door stayed closed.

I thought I’d feel relief.

Instead, the room felt emptier.

After a few days, Elise asked softly, “You talked to him, didn’t you?”

“Yes,” I said.

She nodded. “I can’t tell you what to do. But I’ve never seen anyone show up the way he did.”

That night, alone with Iris, I whispered, “Do you want him here? Because I don’t know what the right thing is anymore.”

She didn’t answer.

A week later, I went to an AA meeting on Oak Street.

Ray stood up and said, “I’m Ray, and I’m an alcoholic. And I put a teenage girl in a coma.”

After the meeting, I told him I didn’t forgive him. He said he didn’t expect that. But I told him he could come back to read. Only that.

The next day at three, he stood in the doorway, waiting for permission.

I nodded.

Weeks passed.

Then one afternoon, Iris squeezed my hand.

Then again.

The room exploded into motion.

She woke up.

Recovery was brutal. Physical therapy. Pain. Rage. Days she refused to try. Days she cried over her legs.

When we told her the truth, she listened quietly.

“I don’t forgive you,” she told Ray.

“I understand,” he said.

“But don’t disappear,” she added. “I don’t know what that means yet.”

Almost a year after the crash, Iris walked out of the hospital with a cane.

“You ruined my life,” she told him.

“I know,” he said.

“And you helped me not give up on it,” she added.

Every year now, at exactly three, we meet for coffee.

We don’t forgive.

We don’t forget.

We just sit with what happened, and choose to keep going anyway.